Abe Callard’s Ghost Writer is a short film made completely using Google Maps Street View mode. We can see a dialectic between the “new” and the “old”, between its form and story, and then see the young director Abe’s gesture as an auteur in the era of new media.

There is no lack of new faces at the 8th Beijing International Short Film Festival (BISFF) in 2024, and Abe Callard is one of them. His short film Ghost Writer had its world premiere in the international competition. At only 20 years old and still pursuing a philosophy degree at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), Abe is, in fact, far from inexperienced. His feature film Early Riser, completed in 2024, was included in Dan Sallitt’s list of the ten best films of the year. This young filmmaker possesses a rare and striking maturity, observing the world with an incomparable calm and steady gaze. During the BISFF screenings, Abe could always be found sitting silently in the back right of the UCCA exhibition hall, watching almost all the films shown at the festival with a quiet and composed demeanor.

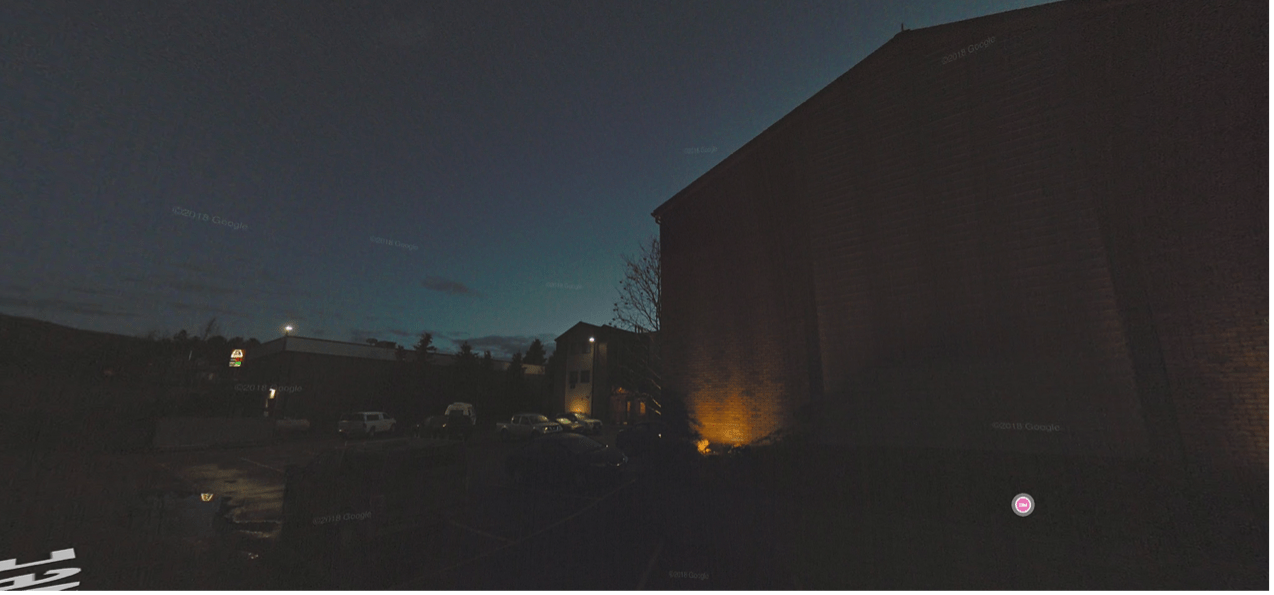

His short film Ghost Writer gives a similar impression. Using images entirely from Google Maps Street View and a first-person voice-over, the film tells a simple yet mysterious story. The protagonist is a ghostwriter who arrives in the town of Grand Marais on a mission to write the autobiography of a legendary rock musician, Lars Benson. After three days of investigation, the protagonist becomes disheartened, as there seems to be no trace of Lars Benson’s existence in the town.

To some extent, the film establishes a dialectic between the “new” and the “old.” Formally, it belongs to the era of new media, yet it connects to classical cinema through its noir narrative structure. The Google Maps Street View imagery introduces the visual language of the digital interactive interface, whose basic grammar differs greatly from the audiovisual construction of traditional films. Yet the film does not abandon narrative; on the contrary, its storytelling possesses a marked literariness. The first-person narration makes the experience of watching the film akin to reading a twentieth-century American short story, easily evoking the works of Raymond Carver or Paul Auster. They share an existential anxiety and a coolly detached narrative style that bridges the gap between film and literature.

This dialectic of the “new” and the “old” can also be understood as a dialectic between two kinds of perceptual experience shaped by Abe as the creator. First, the ghost writer in the story, a flâneur as defined by Baudelaire and Benjamin, constantly wanders through the strange, deserted town. As an ideal spectator and observer, he watches the world while remaining detached from it. Abe’s story is narrated in the first person. From his perspective, the town appears haunted, yet the people and things he encounters in fact become mirrors of his own subjectivity.

The second kind of perceptual experience arises from the film’s form. The Google Maps imagery constructs not only the vision and body of the ghost writer, but also that of a “data cowboy” traversing cyberspace—the image of a user navigating a digital virtual space. When the mouse cursor drags and rotates the viewpoint, when the sky or a building is magnified on the screen by zooming in, we are not only within the body of the ghost writer; we can also faintly sense Abe’s presence—the body of the filmmaker sitting in front of a computer, operating the mouse, remotely traveling through Google Maps’ Street View mode, freely exploring. And it is through this pure, unbounded exploration that the story naturally comes into being.

No matter the degree of self-awareness the creator possesses, this is undeniably a film that belongs to the new media era and speaks in the language of new media. The interactive interface and the act of roaming through cyberspace have become integral to the cultural cognition of both producers and consumers today. Moreover, on a practical level, the footage acquired through the use of new media offers an affordable mode of film production, especially for low-budget independent filmmakers.

Although Abe repeatedly emphasized the primacy of story over form in post-screening discussions, he nevertheless reveals the sensibility of an auteur of the new media era through his work. On the surface, Ghost Writer and Abe’s feature film Early Riser appear entirely different—in other words, they differ in the visual style—but one can still clearly sense the same auteurist attitude. Stéphane Delorme describes this kind of choice—one that transcends questions of form—as the auteur’s gesture (le geste), meaning a relationship with the world and a distinct perspective.

Abe’s gesture is full of secrets. In his films, each character, to varying degrees, refuses to open themselves to the camera or the audience, including the protagonist. Even among the characters, communication is often withheld; they choose solitude instead. When dialogue does occur, the image occasionally shifts toward irrelevant subjects—such as the sky—suggesting a drift in the characters’ gaze or attention. Is this emphasis on intersubjectivity part of Abe’s gesture as a creator? Gesture, like writing, is a choice—a “general choice of style, temperament, etc.” (as Roland Barthes explains)—and a responsibility to intervene in the world.

Gesture is not as easy to articulate in words as in style. It represents an extension of auteur theory into the metaphysical realm. It cannot be directly seen, but it can certainly be perceived. Gesture is the portrait shared by the auteur and his work—a deep signature. Compared to gesture, style is dangerous. We often see certain film auteurs become captives of pretension and gimmickry in their excessive pursuit of style, thereby losing their gesture. Gesture is an ethic—an ethic of form, an ethic of mise en scène.

Abe’s ethic lies in his ability to maintain an appropriate distance from his characters while roaming through space—like the unbridgeable gap between the ghost writer and Lars Benson, or between the two different Grand Marais towns. It is precisely this distance that creates delicate connections among characters, between the characters and the author, and between the characters and the audience. If a young filmmaker can already demonstrate his potential as an auteur at the age of twenty, it is because he has revealed a vibrant, evolving gesture. When we watch his films, we are, in essence, engaging in a dialogue with the auteur and his attitude toward the world.