Featuring 331 films, the Beijing International Short Film Festival (BISFF) expands year by year, showcasing a broad overview of short films, with occasional mid-length and feature-length works tucked into sidebars. In its ninth year, the festival made a leap, transitioning from an event organised in art galleries and foreign cultural institutions to one held in a commercial cinema. However, things did not go as planned. Therefore, this report is written in two parts. In the first part, I discuss the background of what happened, and in the second, I delve into the foreground—that is, the films showcased at the festival.

Background 1: The environment

During the ten-plus years since I started writing about cinema in China, I used to often think about the independent film movement of the early 2000s, especially the film exhibitions of that era such as the Beijing Independent Film Festival and the China Independent Film Festival. Compared with the 2000s mainstream Chinese cinema or official film festivals (which received Chinese government funding), there is a very broad body of scholarly and journalistic coverage of these grassroots-organised film festivals. This coverage inescapably created a slightly utopian image in my mind of what happened on site—screenings of exciting films that I had no way to access; events organised and attended by a community of people who shared a goal of changing the film environment in China and using cinema to discuss contemporary social phenomena.

This image of grassroot film festivals captured the imagination of those like me who wished to participate in these festivals and see the films showcased but had the bad luck of being born too late. In particular, the closure of the Beijing Independent Film Festival—with police cutting off electricity at the screening venue, the struggle to organise remaining screenings for guests, and the discussions recorded in the film documenting the moment, A Filmless Festival—seemed especially heroic. Through my interest in researching film festivals in China, I have continued to ask people who were there, to juxtapose this image with a more personal and subjective account.

A decade after the crackdown on independent film festivals in China, there seemed to be a relapse to that moment. However, in 2025 there are no ready answers as to what has happened and why. Following the institutionalisation of art cinema in China, the film environment does not look the way it did ten years ago. It continues to commercialise and professionalise, in tune with the global film market. Different stakeholders in China emerge – sales agents, distribution companies, curators. There is a fierce competition for different forms of capital – not only financial, but also social (connections with filmmakers and investors) and symbolic (premiere status, upholding principles such as “art for art’s sake” and freedom of speech). Therefore, in recent years rather than a top-down government decision—such as film censorship or police intervention—the reports calling for the closure of the festival often come from members of the audience or film industry insiders themselves. Secondly, there are different new types of film festivals emerging. The three examples below represent three different models of film festivals, yet all of them encountered a similar situation of an interruption in proceedings.

Background 2: On site

In early November 2025 there were three Chinese film festivals about to take place. First: Wuhan Bailin Film Festival (October 31 – November 9) in Central China in its fifth year.[1] Second: inaugural edition of the IndieChina Film Festival in New York (November 8 – November 15) at the 100 Sutton Event Space. Finally, the 9th Beijing International Film Festival (November 8 – November 16). While the Wuhan Bailin Film Festival and BISFF are organised by overseas-educated Chinese born in the late 1980s and 1990s, the IndieChina Film Festival was the idea of Zhu Rikun, one of the figures behind grassroots film festivals in Beijing in the 2000s.

Wuhan Bailin is a cinephile and art cinema-oriented film festivals focusing on full-length fiction films, previously selected by festivals at the top of the film festival circuit hierarchy: Cannes, Venice, Berlinale, Locarno, Sundance.

ChinaIndie programme featured films previously screened at independent film festivals between the early 2000s and the mid-2010s as well as several contemporary works, Zhu Rikun drawing on his vast film collection and social networks.

BISFF is focused on exploring different forms of cinema and film language while remaining very inclusive and accessible for all types of audiences. Each year, the programming team goes through thousands of films submitted via open call rather than relying on the titles already travelling the film festival circuit. From 10% to 20% of the films selected are world premieres. BISFF is the most inclusive and the most international of film festivals in China, keeping in touch with international filmmakers and audiences through social media and regularly updated website.

Then an avalanche of closures began. On 5 November, the Wuhan Bailin Film Festival was shut down midway. A friend who was attending the festival speculated that a member of the audience had reported the festival to the police because one of the films contained an explicit sex scene. When I spoke to the organisers, however, they said this was not the case: the report was not triggered by any specific film, but by the entire programme.

For the IndieChina Film Festival in New York, the cancellation was reported on widely in English-language media, the reason for cancellation reportedly being the filmmakers pulling out their films from the lineup.[1] Zhu Rikun continued to post photos of empty cinemas on the festival’s official Instagram account in protest the cancellation of the festival. The key question is if the coverage in New York Times or The Guardian would appear if the festival took place? The cancellation and the act of protest is a gesture that always brings attention and contributes to myth-building.

As for BISFF, it was originally scheduled to take place from 8 to 16 November 2025, with most screenings and the festival centre located at the Lumière Pavilions (卢米埃北京芳草地影城), alongside Hey Town Art Center (黑糖盒子) and the festival’s usual partner venue, the French Culture Centre. Whereas in previous years all screenings had been free, this year tickets were sold at the standard price of 60 RMB (around 7,5 EUR) for screenings in cinemas and 50 RMB (around 6 EUR) for the ones held in the art centre.

There were 40 international guests travelling to Beijing, many being young filmmakers for whom BISFF was the first big international film festival their films have been invited to. Throughout the years BISFF programmers managed to search out some of the most promising film talents, going through thousands film submissions. Lumière Pavillions, meanwhile, is in desperate need of the audience cultivated by BISFF. It had been losing money daily, with the cinema attendance rarely exceeding ten people per screening.

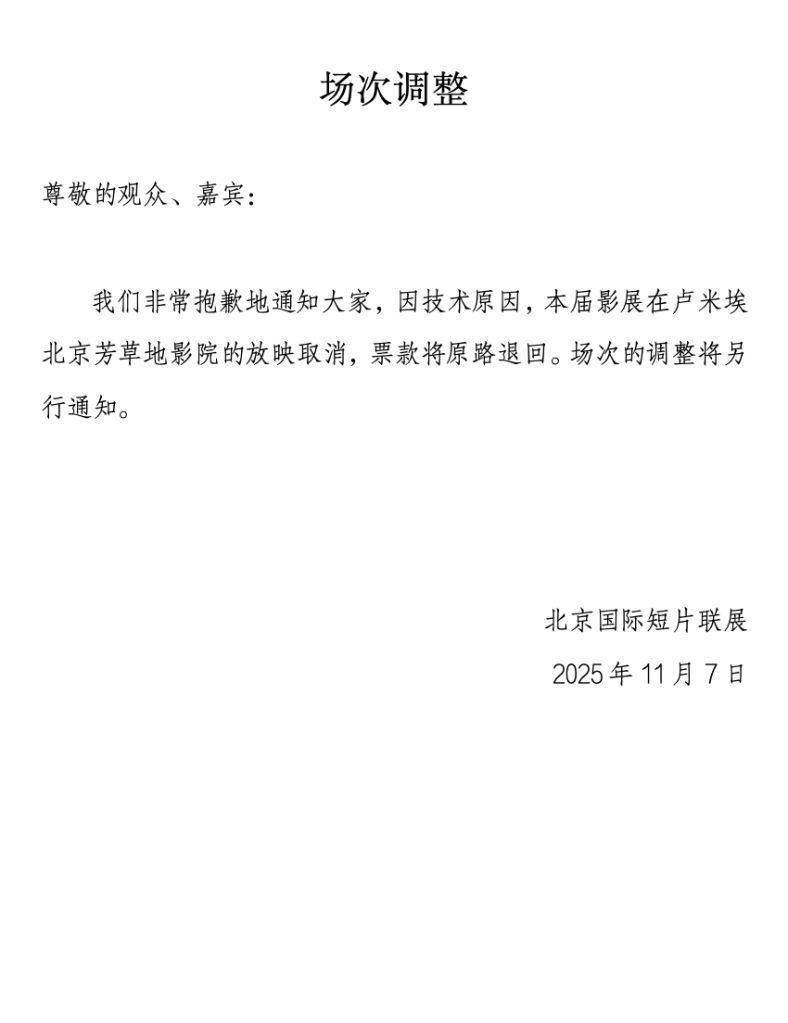

On the night of 7 November, close to midnight, the organisers announced on WeChat that the screenings at Lumière Pavillions and the art gallery were cancelled. Screenings had been scheduled to begin early the next morning, and a small group of cinephiles had already arrived at Hey Town Art Center, unaware of the cancellation. When I arrived, the organisers were on site apologising to the audience. It was an unusually sunny morning, sharply contrasting with the bleak situation and the subdued mood of both cinephiles and organisers. They were exhausted from this labour of love. Having curated more than 300 films, the cancellation was heartbreaking.

The festival had been reported to the police as “illegal” even before it began, making it unlikely that a member of the audience was responsible. Rather, as the organisers suspected, the report may have come from an industry insider—a fellow film festival organiser—someone intimately familiar with the regulatory loopholes, such as additional procedures or tax issues, that arise when a festival transitions from free screenings to commercial ones.

Yet, the epic point of the story here is not the closure but the continuation of the festival regardless of the report. The performance art here is not that of a protest, but of an improvisation. In the following days, BISFF organisers managed to find alternative screening venues for almost the entire programme. European cultural institutions refused to screen films that were not connected to a national cultural agenda or to their national film industry in any way—through co-production or language. It was the Korean Cultural Centre that saved the day by agreeing to screen the Sinophone competition films and parts of the international section that were not accepted by Italian, French, or other regular BISFF venues like the Goethe-Institut, which instead accepted the Greenpeace-sponsored programme centred on environmentalism. The festival finished on November 20th without any closing ceremony since most of the guests already left and the banquet meant additional costs.

When I think of Ding Dawei, there is often an image that pops into my head. During our conversations over the past three years, his signature comment on a film or on a situation (at least the one I remember most clearly) was: “What’s the point?” Said in English, and with a certain degree of self-satisfaction that only a seasoned film critic — in Polish I would say a stary wyjadacz (“old hand,” or, in a more literal translation, “old eater”) — could convey. After almost a decade (and perhaps increasingly because of the years that have passed and the editions that have been organised), there is still a point to BISFF. Also, because each year the films screened at the festival make me care about cinema anew.

Foreground 1: Medium

What about the films, then? It is impossible to get a grasp of the entire programme, even without the screening schedule changing from one day to the next. The programme is divided into different sections to help navigate the ocean of titles. In addition to the International Competition and Sinophone Competition, there is Echo for archival films, Aurora for the Sinophone films on media and mobility, NOVA competition for debut films or films about adolescence, Future Ethics with films on environmentalism, Siphon for experimental films, Phase with films on feminism, Prisma dedicated to identity, Neutron with a selection of mid-length films, Astro for the retrospective, and the special programme War-Image-War, a collection of cinematic images of war and reflection on war through the medium of cinema.

What does cinema do today, and for whom? Attending a short film festival easily shows that everyone makes their own film festival out of the abundance of curated films. Therefore, what follows is not a general overview. I write about any title that left a significant memory or a thought in my mind. Although I had seen blocks of the international competition and the NOVA competition beforehand, in my mind it seems the festival started with the medium-length Avis de passage (2025, dir. Ferdinand Ledoux). In the film, a young filmmaker returns to the footage she shot while being in a relationship that has since fallen apart. The film is filled with close-ups, footage shot from a window, and images of daily life. Instead of being a tool of intimacy, the camera rather allows for maintaining distance from the partner and the life they share. While she tries to become a filmmaker and complete a project while being in the relationship, in the end she keeps returning to one short, blurry, underlit video—the only one that has both of them in the shot—filmed nearly at the end of their relationship. Avis de passage grasps the moment in which one knows the relationship is over, somehow feeling it in the bones that this is the last kiss or the last time you share an apartment as a couple.

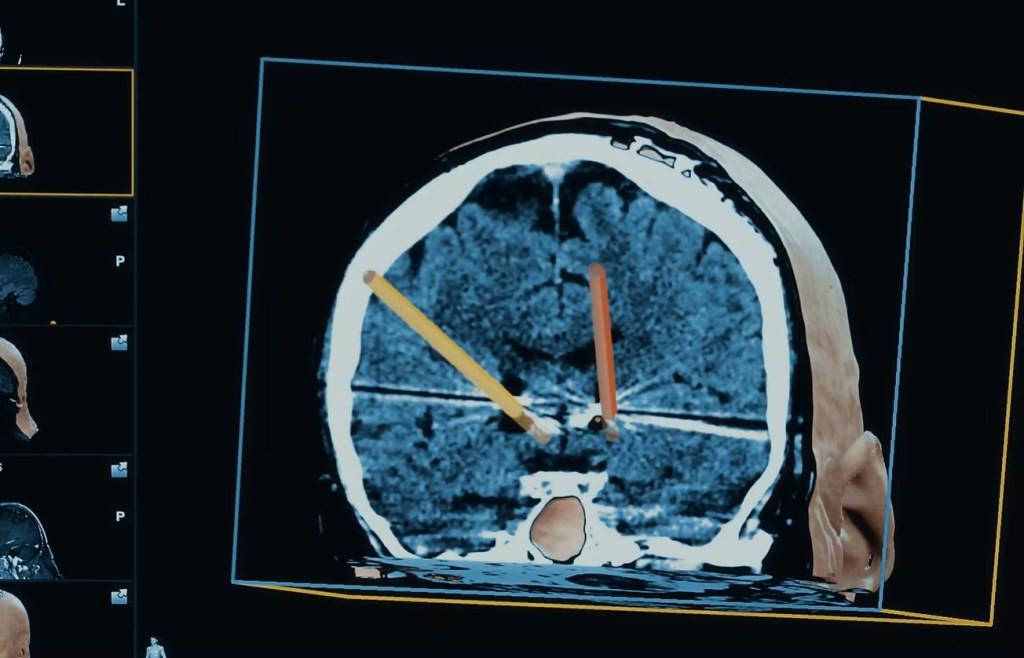

Another film that left me deep in thought was The Blue Flower in the Land of Technology, directed by Albert García-Alzórriz. In recent years, there have been several films set in hospitals, most notably Claire Simon’s documentary Our Body and Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor’s De Humani Corporis Fabrica (2022) in which they use medical visualisation as a chief mode of expression. However, none of the directors mentioned above actually took the position of a stakeholder in the hospital situation, either a patient or a healthcare worker. Even though The Blue Flower in the Land of Technology is not a personal account, Albert García-Alzórriz worked on the film from the perspective of someone terminally ill, subjected to check-ups, whose body is viewed through the lens of medical imagery. In the film, he focuses on a middle-aged male fellow patient going through brain surgery and a period of recovery, trying to restore the nervous system to functionality. However, in one scene we see a perspective from the operating table—blurry and shaky. Filmmaking becomes a way to experiment with one’s own experience of pain and helplessness, making sense of what is happening to the body, with the camera being the organ that still works, the one the filmmaker can find comfort in. In two of the mid-length films, directors confronted and communicated their emotional and physical pain in the most transgressive way through the use of cinema and its ability to evoke empathy in viewers.

Moving forward, there is a type of film that I have a special liking for: those explicitly using a desktop and interfaces of various kinds to show a process of research and storytelling, or those revolving around the medium itself. In the international competition, A Real Christmas, filmmaker Justin Jinsoo Kim tries to find any information about Lee Kyung Soo, a Korean War orphan adopted by a U.S. Navy officer in the 1950s. Instead of telling a story based on what he has found, he lets the archives speak for themselves by showing the process of research. Lee’s image was used in various official media to further U.S. propaganda during the Cold War, especially on the cultural front. In news coverage, Lee, as a small boy, is shown celebrating Christmas, the holiday most strongly disseminating Western culture and Christian family values, especially in the Protestant-It’s a Wonderful Life-style as it is known in the U.S. However, the information becomes less and less available as Lee gets older, until we can only speculate about what his life looked like. The loudness of U.S. propaganda contrasts with the silence of the archives once Lee’s story stopped being useful for the official narrative.

Colombian filmmaker Sofía Salinas Barrera, in Frequently Asked Questions, also uses the desktop, in addition to excerpts from films and her own footage, to try to find an idea behind the images she has recorded so far. Footage becomes a means of introspection, an inquiry into how she perceives the world. On the sidelines, the question emerges: why does someone want to become a filmmaker? What is the point? The urge to record what one notices in the world is a shared feature of all humans, now made obvious through reels on social media. Now, the challenge is to answer the question of the profession when the means of production are democratised. What makes a person a filmmaker now? Is it the mode of exhibition and distribution of the works? The social circles they are a part of? There are people who migrate between realms—social media, cinema, streaming platforms—but it seems one’s work has to be ingrained in one tradition in order not to become merely a storytelling gimmick produced through the use of different media.

Coherence – or decorum as she keeps repeating in the short – are what I appreciate most about Julia Mellen’s Abortion Party. For her, the question of being a filmmaker is very straightforward. She is explicit that she makes films to make a living, to apply for funding, or to get another residency—a common reflex among people who have had no other choice but to support themselves through scholarships to be able to do what they want in life. However, this does not mean that filmmaking is forced or merely serves economic interests or reputational pursuits, as can be sensed in many projects that were originally short films and, through a series of mouldings at various film markets and pitching sessions, eventually emerge as full-length films on the festival circuit, trying hard to conceal how painful the production process was.

Abortion Party on the other hand is made with DIY spirit, and this punk attitude can be sensed all over the film. For Julia Mellen, virtually anything can become material for a film, including an abortion party she threw several years ago while still living in the U.S. Formal imperfections and a certain crudeness are what bring the film closer to reality, because the urge to tell a story overrides the lack of professional equipment.

This straightforwardness is shared by Description of a Leave 一场分手纪实 (dir. Xie Yunlong), screened in the Aurora Sinophone Competition. It reminded me a lot of a type of film that is no longer made: postmodernist comedy dramas with a romantic subplot, such as Keep It Cool 有话好好说 (1997, dir. Zhang Yimou). Description of a Leave is a simple story about a teenage couple talking about breaking up; the editing is fast-paced and the camera angles non-orthodox. Even though it may now seem like a nod to 1990s postmodernist cinema with a touch of social media aesthetics, Description of a Leave stood out among the films selected for the Sinophone competition due to its unpretentiousness and playfulness.

Foreground 2: Becoming

On the other side of the spectrum are films that dazzle with production quality and a classic fiction narrative. In the NOVA competition, A Sky So Low (Un ciel si bas), filmmaker Joachim Michaux returns to one of the most transgressive moments in Europe’s recent history: 1989 and the fall of the Berlin Wall. The short film revolves around a simple story of a young man who travels from France to Bruxelles to see a girl with whom he had a summer fling. He has only her work address, but when he gets there—a bar with a small pension in downtown Bruxelles—he finds out that she no longer works there. He decides to stay and look for her, meanwhile befriending Damian, an English journalist reporting on UFO sightings, and the barmaid Rosie. The three friends dive deep into the Bruxelles rave scene, the most likely place to find the missing girl.

Michaux combines elements of sink realism, science fiction, coming-of-age, and period drama. He manages to create a highly immersive atmosphere, specifically through the use of sound and music. Watching A Sky So Low, it feels as if I were taken back to 1989—the time that suddenly seemed to have opened endless possibilities of connection between the Eastern and the Western blocs, but building it on the premise of one “winning over” the other (the “winning” ideology being capitalism and liberal democracy as opposed to socialism and communism) resulted in an illusion that the dispute had been solved. Instead, as current political events show very clearly, it brought resentment and hard feelings—like the end of any romance does.

Like A Sky So Low, That Summer I Got Accepted to University (Тем летом я поступил, dir. Alexandr Belov) has the production quality of a feature-length fiction film, but its story works best in the short format. Belov focuses on the tension between two school friends—one blond-haired and machoistic, the other maroon-haired and sensitive—who spend the summer holidays together in the house of the former before the latter goes to university. The omnipresence of domestic violence is felt beneath the calm countryside landscape, where the blond-haired boy lives with his aggressive father and numb mother. What I found particularly striking about That Summer I Got Accepted to University is the way the camerawork neutralises emotions that might otherwise feel excessive, making the characters seem pathetic. The camera often pans through space without focusing on either character. However, when it does settle on them, their emotions become almost palpable—heartbreaking and perfectly bittersweet.

Finally, the Norwegian short film Lumber (Hogst, dir. Einar Henriksen), screened in the Future Ethics programme, surprised me with its simplicity, its conceptual weight matched by impeccable visual aesthetics. We follow a hiker moving through a forest massacred by logging activity. The longer we observe, the less transparent and “natural” the images appear. Cut tree trunks begin to resemble hand stumps, bare branches look like hairless heads, and a feeling of abjection and horror slowly creeps in.

Perhaps watching Silent Friend (Stille Freundin, 2025, dir. Ildikó Enyedi) made me more sensitive to the ways plants and trees exist, feel, and interact with the world. Lumber shows the violence humans inflict on the environment without words, simply by being itself—speaking in the language of trees that absorb the environment in its entirety: emotions, the warmth of the sun, minerals—without compartmentalisation and without words cutting the world into pieces.

Parting words

As in previous editions of the BISFF, the jury selections ultimately reinforced my sense of having participated in a self-curated festival experience. I viewed most of the award-winning films only after the festival had ended, primarily out of curiosity regarding the criteria and preferences guiding the juries’ decisions. However, as these films did not form part of my lived experience of the festival itself, they fall outside the scope of this report. Therefore, my account ends here.

[1] On the other hand, nowadays, as tensions between China and the US increase across multiple areas—along with heightened fears of Chinese espionage and infiltration—intervention come from either government. The independent online newspaper The China Project was closed after both US and Chinese authorities accused its journalists of biased coverage. While explaining the reasons for closure, the editor-in-chief Jeremy Goldkorn mentioned that the newspaper had been “accused many times in both countries of working for nefarious purposes for the government of the other. Defending ourselves has incurred enormous legal costs, and, far worse, made it increasingly difficult for us to attract investors, advertisers, and sponsors.”

[1] In the last four years, Wuhan Bailin has come to be viewed by cinephiles in China as one of the most professional international film festivals in the country, mainly for three reasons. Firstly, it screens foreign full-length feature films. In 2025, it even snatched the Chinese premiere of Cannes titles (Nadav Lapid’s Yes or Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke’s A Useful Ghost) away from official film festivals such as Hainan Island IFF, which typically programme films selected by Cannes, Berlinale, or Venice. Secondly, it was organised in a commercial cinema. Thirdly, the festival dates were announced several months in advance, something that almost never happens with official film festivals, because their funding requirements are higher and are often secured only at the last minute; consequently, their dates are sometimes announced to the public as late as one week before the planned opening of the festival.